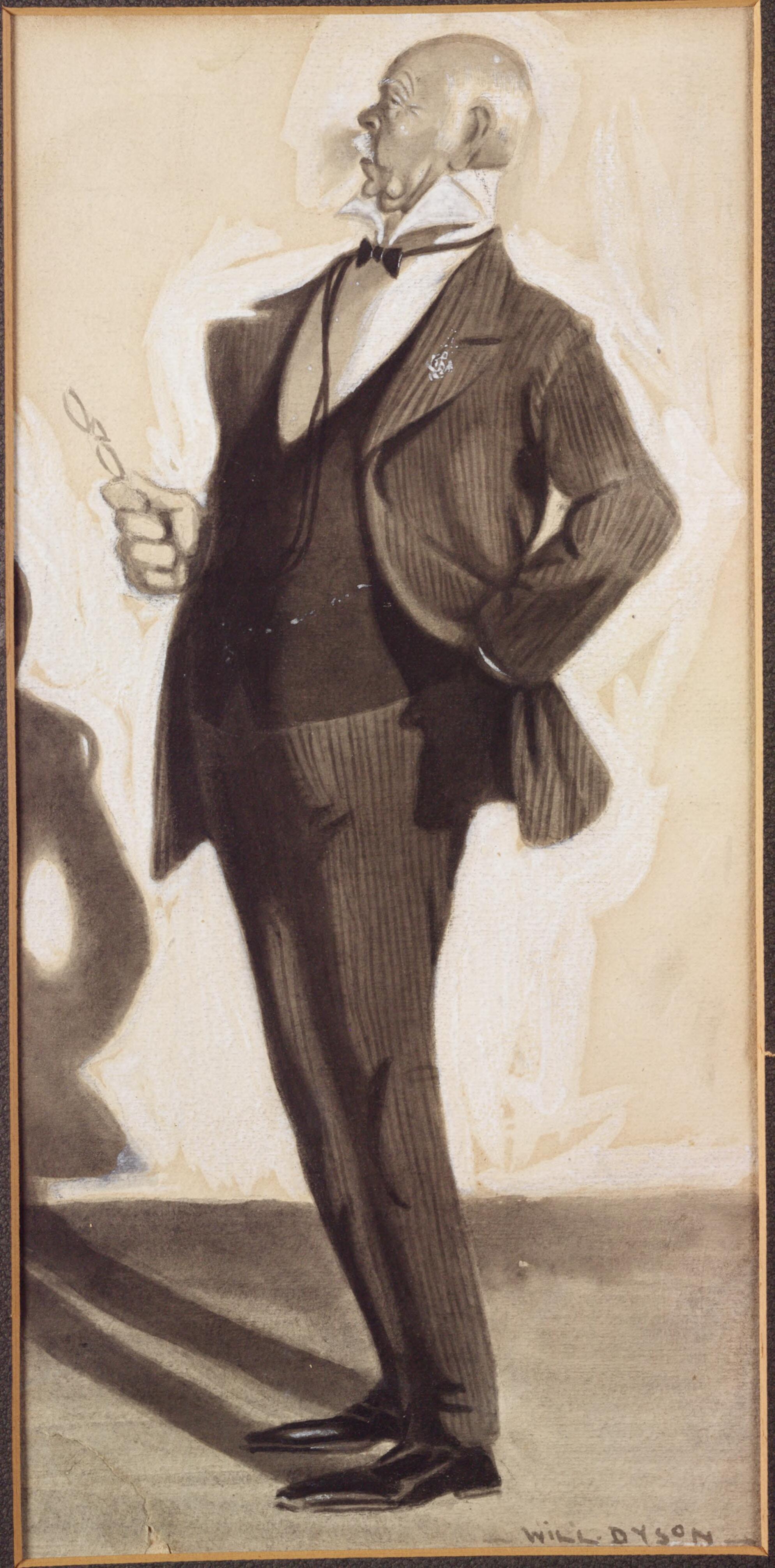

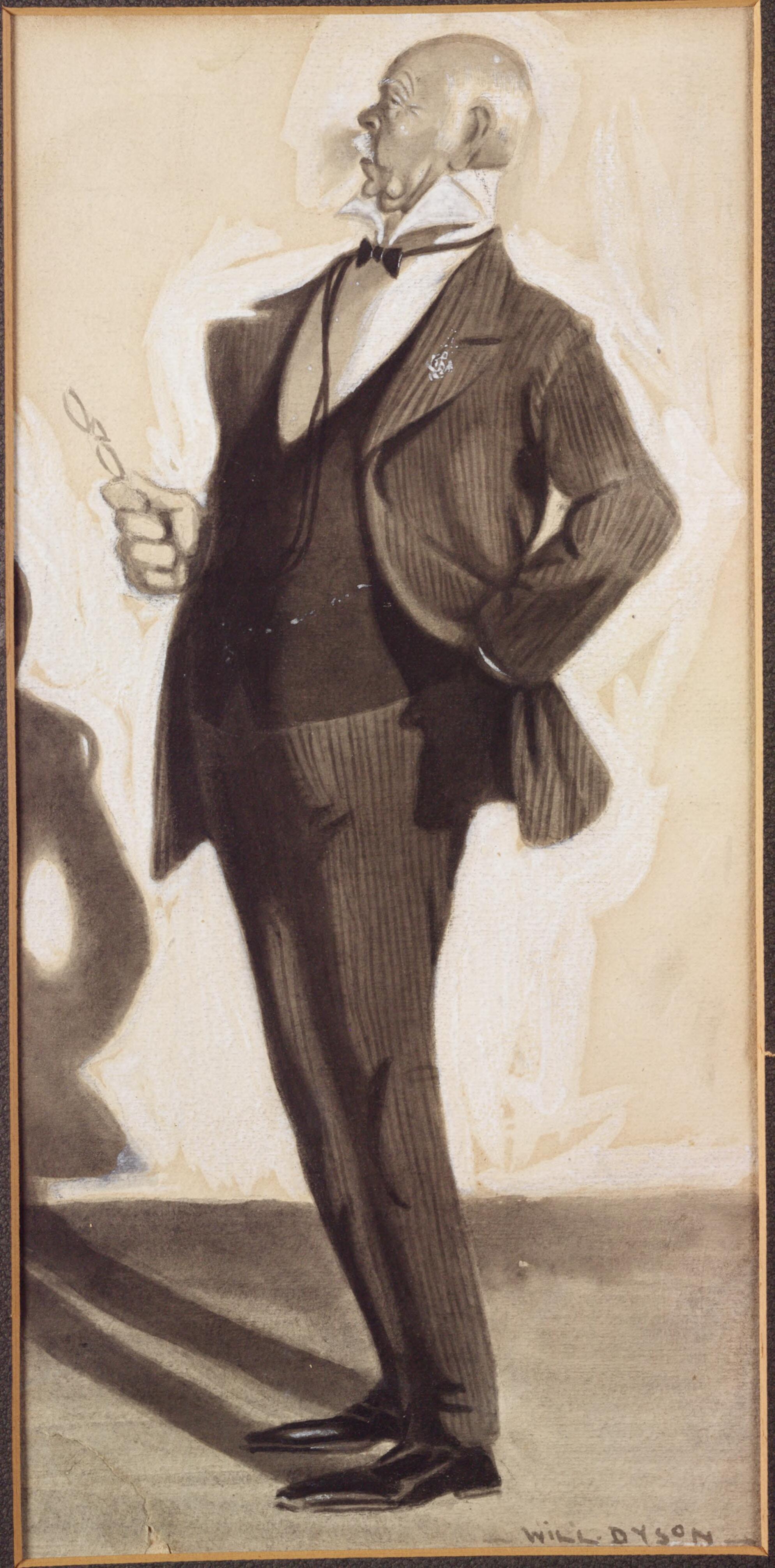

Josiah Symon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Josiah Henry Symon (27 September 184629 March 1934) was an Australian lawyer and politician. He was a

In March 1881, Symon was made

In March 1881, Symon was made

Symon stood for election to the

Symon stood for election to the

Symon died in 1934, and was given a

Symon died in 1934, and was given a

Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

for South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

from 1901 to 1913 and Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-GeneralThe title is officially "Attorney-General". For the purposes of distinguishing the office from other attorneys-general, and in accordance with usual practice in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions, the Aust ...

from 1904 to 1905.

Symon was born in Wick, Caithness

Wick ( gd, Inbhir Ùige (IPA: �inivɪɾʲˈuːkʲə, sco, Week) is a town and royal burgh in Caithness, in the far north of Scotland. The town straddles the River Wick and extends along both sides of Wick Bay. "Wick Locality" had a population ...

, Scotland. He immigrated to South Australia in 1866 and became one of the colony's leading barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

s. He was appointed Attorney-General of South Australia

The attorney-general of South Australia is the Cabinet minister in the Government of South Australia who is responsible for that state's system of law and justice. The attorney-general must be a qualified legal practitioner, although this wa ...

in 1881, serving only a few months, and won election to the Parliament of South Australia

The Parliament of South Australia is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of South Australia. It consists of the 47-seat House of Assembly ( lower house) and the 22-seat Legislative Council (upper house). General elections are ...

in the same year. Symon supported the federation movement and won election to the Senate at the 1901 federal election. He served as Attorney-General in the Reid Government (1904–1905). After his death he donated his extensive personal collection to the State Library of South Australia

The State Library of South Australia, or SLSA, formerly known as the Public Library of South Australia, located on North Terrace, Adelaide, is the official library of the Australian state of South Australia. It is the largest public research l ...

.

Early life

Symon was born inWick

Wick most often refers to:

* Capillary action ("wicking")

** Candle wick, the cord used in a candle or oil lamp

** Solder wick, a copper-braided wire used to desolder electronic contacts

Wick or WICK may also refer to:

Places and placenames ...

, a town in the county of Caithness

Caithness ( gd, Gallaibh ; sco, Caitnes; non, Katanes) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded by ...

in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

, in 1846. He was educated at Stirling High School

Stirling High School is a state high school for 11- to 18-year-olds run by Stirling Council in Stirling, Scotland. It is one of seven high schools in the Stirling district, and has approximately 972 pupils. It is located on Torbrex Farm Road, ...

, where he was the dux

''Dux'' (; plural: ''ducēs'') is Latin for "leader" (from the noun ''dux, ducis'', "leader, general") and later for duke and its variant forms (doge, duce, etc.). During the Roman Republic and for the first centuries of the Roman Empire, '' ...

in 1862, before attending the Free Church Training College

The Free Church Training College was an educational institution in Glasgow, Scotland. It was established by the Free Church of Scotland in 1845 as a college for teacher training.

In 1836, David Stow had established a normal school in Glasgow but ...

in Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

. His brother, David Symon

David Culross Symon (12 March 1858 – 21 March 1924) was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia from 1890 to 1892, representing the seat of South Fremantle. He was born in Scotland, lived in Australia from 1881 to 1892, and ...

, was a member of the Legislative Assembly of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

. He was a distant cousin of Magnus Cormack

Sir Magnus Cameron Cormack Order of the British Empire, KBE (12 February 1906 – 26 November 1994) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Liberal Party of Australia, Liberal Party and served multiple terms as a Australian Senate, ...

, who was also born in Wick and served as President of the Senate

President of the Senate is a title often given to the presiding officer of a senate. It corresponds to the speaker in some other assemblies.

The senate president often ranks high in a jurisdiction's succession for its top executive office: for e ...

in the 1970s.

In 1866 he emigrated to South Australia and was employed as an articled clerk

Articled clerk is a title used in Commonwealth countries for one who is studying to be an accountant or a lawyer. In doing so, they are put under the supervision of someone already in the profession, now usually for two years, but previously thre ...

with his cousin, J. D. Sutherland, a solicitor in the city of Mount Gambier

Mount Gambier is the second most populated city in South Australia, with an estimated urban population of 33,233 . The city is located on the slopes of Mount Gambier, a volcano in the south east of the state, about south-east of the capital Ad ...

. The leader of the South Australian Bar Association at the time (and a future Chief Justice of South Australia

Of the judges of the Supreme Court of South Australia, , 14 had previously served in the Parliament of South Australia Edward Gwynne, Sir Richard Hanson, Randolph Stow, Sir Samuel Way, Sir James Boucaut, Richard Andrews, Sir William Bundey, S ...

), Samuel Way

Sir Samuel James Way, 1st Baronet, (11 April 1836 – 8 January 1916) was an English-Australian jurist who served as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of South Australia from 18 March 1876 until 8 January 1916.

Background

Way was born in P ...

, noticed Symon's work and invited him to join his firm. Symon, having completed his studies, was called to the bar in 1871, and admitted to practice as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

. In 1872, after the death of one of the partners at Way's firm, Symon became a partner alongside Way. In 1876, Way was appointed as a judge, and Symon bought out his part of the business.

Colonial politics

In March 1881, Symon was made

In March 1881, Symon was made Attorney-General of South Australia

The attorney-general of South Australia is the Cabinet minister in the Government of South Australia who is responsible for that state's system of law and justice. The attorney-general must be a qualified legal practitioner, although this wa ...

in the Morgan government, although at the time he had not been elected to the Parliament of South Australia

The Parliament of South Australia is the bicameral legislature of the Australian state of South Australia. It consists of the 47-seat House of Assembly ( lower house) and the 22-seat Legislative Council (upper house). General elections are ...

. He was elected as the member for Sturt in the South Australian House of Assembly

The House of Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of South Australia. The other is the Legislative Council. It sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Adelaide.

Overview

The House of Assembly was creat ...

several weeks later. However, the Morgan government lost power on 24 June of that year, and Symon lost his position as Attorney-General. Later in 1881, Symon was made a Queen's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of ...

, and on 8 December of that year he married Mary Cowle, with whom he was to have five sons and seven daughters. In 1884, Symon was offered a judicial position, but he declined to accept it. He travelled to England in 1886, and was offered a nomination for a seat in the British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

, however he declined this opportunity also. In 1887, after returning to Australia, he lost his seat in the South Australian parliament.

He was a highly effective and ruthless advocate: in 1889 he successfully prosecuted the William Hutchison libel case against J. B. Mather and George Ash of The Narracoorte Herald

''The Naracoorte Herald'' is a weekly newspaper first published in Naracoorte, South Australia on 14 December 1875. It was later sold to Rural Press, previously owned by Fairfax Media, but now an Australian media company trading as Australian Commu ...

. In his highly technical argument he succeeded in having evidence from Hansard

''Hansard'' is the traditional name of the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official print ...

and Crown Law documents ruled as inadmissible. Ash (who conducted his own defence) then turned to politics and law, and after his untimely death received glowing tributes from Symon.

Symon was an ardent supporter of the cause of Federation, and frustrated by the apathy the question commonly received in South Australia. He successfully stood as a candidate for the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897-8, and was on the side of the majority in 71 percent of its divisions; a higher percentage than the great bulk of delegates. In the subsequent struggle to win the support of the electorate for the proposed federal constitution, he was a significant behind the scenes player, sought out by Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was an Australian politician who served as the second Prime Minister of Australia. He was a leader of the movement for Federation, which occurred in 1901. During his three terms as prime ministe ...

, for example, to arrange funding for Federationist candidates in the NSW general election of 1898. Symon was knighted on the day of the proclamation of the new Commonwealth.

Federal politics

Symon stood for election to the

Symon stood for election to the Australian Senate

The Senate is the upper house of the Bicameralism, bicameral Parliament of Australia, the lower house being the House of Representatives (Australia), House of Representatives. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Chapter ...

at the 1901 election for the Free Trade Party

The Free Trade Party which was officially known as the Australian Free Trade and Liberal Association, also referred to as the Revenue Tariff Party in some states, was an Australian political party, formally organised in 1887 in New South Wales, ...

, and was placed first overall by the voters of South Australia. He was made leader of the opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the opposition is typically se ...

in the Senate, and was a leader within the Free Trade Party on tariff

A tariff is a tax imposed by the government of a country or by a supranational union on imports or exports of goods. Besides being a source of revenue for the government, import duties can also be a form of regulation of foreign trade and poli ...

policy. After being elected to the Parliament, he stood down from his position as a member of the council of the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, a position he had held since 1897. In 1902, he was involved as the defense council in the highly publicised murder of Bertha Schippan

The murder of Johanne Elizabeth "Bertha" Schippan (January 1888 – 1 January 1902) is an unsolved Australian murder. The victim, the youngest child in a large Wends, Wendish family, resided in the South Australian town of Towitta, South Austral ...

trial. At the 1903 election he again topped the poll for the Senate in South Australia. When the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is Australia's apex court. It exercises Original jurisdiction, original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified within Constitution of Australia, Australia's Constitution.

The High Court was established fol ...

was created in late 1903, Symon was mentioned in the press as a possible judge of the court, although ultimately he was not appointed. From August 1904 to July 1905 he was the Attorney-General of Australia

The Attorney-GeneralThe title is officially "Attorney-General". For the purposes of distinguishing the office from other attorneys-general, and in accordance with usual practice in the United Kingdom and other common law jurisdictions, the Aust ...

in the Reid Ministry.

Symon was renowned as a tough and uncompromising politician. He has been described as both an "eloquent and emotional speaker" and often "abrasive and argumentative." Late in 1904, Symon was involved in a dispute with the judges of the High Court. In the court's early years, its official home was a courtroom in Melbourne, although it often sat at the court in the Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst

Darlinghurst is an inner-city, eastern suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. Darlinghurst is located immediately east of the Sydney central business district (CBD) and Hyde Park, within the local government area of the City of Sydney. I ...

. Justices Barton and O'Connor lived in Sydney, but Chief Justice of Australia

The Chief Justice of Australia is the presiding Justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia. The incumbent is Susan Kiefel, who is the first woman to hold the position.

Co ...

Sir Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, (21 June 1845 – 9 August 1920) was an Australian judge and politician who served as the inaugural Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1903 to 1919. He also served a term as Chief Justice of Queensland and t ...

lived in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, and took a two-day train ride to attend each sitting in Melbourne. When Griffith asked for some bookshelves to be installed in the Darlinghurst courthouse, so that his law library might be moved from his offices in Brisbane, Symon criticised Griffith for holding any sittings outside Melbourne, and began intrusive inspections of the judges' travel expenses. Prime Minister George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales f ...

tried to intervene, and Griffith even took the extraordinary step of delaying scheduled sittings early in 1905. The stand-off was resolved when the Reid government left power, and the new Attorney-General (and future Chief Justice) Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs (6 August 1855 – 11 February 1948) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the ninth Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1931 to 1936. He had previously served on the High Court of A ...

permitted the judges to travel. Later, in 1930, when Symon was president of the Adelaide branch of the Royal Empire Society

The Royal Commonwealth Society (RCS) is a non-governmental organisation with a mission to promote the value of the Commonwealth and the values upon which it is based. The Society upholds the values of the Commonwealth Charter, promoting confli ...

, he was an outspoken opponent of James Scullin

James Henry Scullin (18 September 1876 – 28 January 1953) was an Australian Labor Party politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia. Scullin led Labor to government at the 1929 Australian federal election. He was the first Catho ...

's nomination of Isaacs as Governor-General of Australia

The governor-general of Australia is the representative of the monarch, currently King Charles III, in Australia.Canberra

Canberra ( )

is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The ci ...

in August 1906, Symon joined those supporting it as the location of the national capital, stating that "''the site seems to me an ideal one''".

In 1909, when the Free Trade Party and the Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party or Liberal Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1887 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. The party advocated protective tariffs, arguing it would allow Australi ...

merged to form the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fu ...

, Symon was one of a small group of politicians who did not join, instead remaining in Parliament as an independent. Symon did not hold any other ministerial positions, and eventually left the Senate after losing his seat in the 1913 election. He continued to practice as a barrister until his retirement in 1923 at the age of seventy-seven.

Death and recognition

Symon died in 1934, and was given a

Symon died in 1934, and was given a state funeral

A state funeral is a public funeral ceremony, observing the strict rules of Etiquette, protocol, held to honour people of national significance. State funerals usually include much pomp and ceremony as well as religious overtones and distinctive ...

. He was survived by his wife, his five sons and five of his seven daughters. In addition to bequeathing his library, Symon also left money for the establishment of scholarships at the University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

, Scotch College in Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

and Stirling High School, which he had attended in his youth.

The Canberra suburb of Symonston is named for him.

The Lady Symon Building

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, designed by Woods, Bagot, Jory and Laybourne-Smith and built in 1927 as part of the Union Buildings at the University of Adelaide

The University of Adelaide (informally Adelaide University) is a public research university located in Adelaide, South Australia. Established in 1874, it is the third-oldest university in Australia. The university's main campus is located on N ...

, was named after his wife.

Philanthropy

Symon was a lover of history and literature, and was nominated as a founding member of the Parliamentary Library Committee, which oversees the Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library. Symon, along withTasmania

)

, nickname =

, image_map = Tasmania in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Tasmania in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdi ...

n Senator John Keating, who was also on the committee, suggested that historical documents relating to Australia but kept in the United Kingdom be brought to Australia. In 1907 he visited the Public Record Office

The Public Record Office (abbreviated as PRO, pronounced as three letters and referred to as ''the'' PRO), Chancery Lane in the City of London, was the guardian of the national archives of the United Kingdom from 1838 until 2003, when it was m ...

in London while on a holiday, and campaigned for the logbook

A logbook (or log book) is a record used to record states, events, or conditions applicable to complex machines or the personnel who operate them. Logbooks are commonly associated with the operation of aircraft, nuclear plants, particle accelera ...

s of Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean an ...

's ships HM Bark ''Endeavour'' and HMS ''Resolution'' to be brought to Australia, in the same way that the log of the ''Mayflower

''Mayflower'' was an English ship that transported a group of English families, known today as the Pilgrims, from England to the New World in 1620. After a grueling 10 weeks at sea, ''Mayflower'', with 102 passengers and a crew of about 30, r ...

'' had been taken to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in the United States. Though unsuccessful, Symon continued the campaign on his return to Australia, and in 1909 moved a resolution in the Senate to call for the logs to be brought to Australia. Although the logs were never given to Australia, the original copy of the Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia (or Australian Constitution) is a written constitution, constitutional document that is Constitution, supreme law in Australia. It establishes Australia as a Federation of Australia, federation under a constitutio ...

was brought to Australia in 1990, after campaigning by Prime Minister Bob Hawke

Robert James Lee Hawke (9 December 1929 – 16 May 2019) was an Australian politician and union organiser who served as the 23rd prime minister of Australia from 1983 to 1991, holding office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (A ...

in a tradition which historians link to Symon.

Symon had a massive personal collection of approximately ten thousand books, which he ultimately bequeathed to the State Library of South Australia

The State Library of South Australia, or SLSA, formerly known as the Public Library of South Australia, located on North Terrace, Adelaide, is the official library of the Australian state of South Australia. It is the largest public research l ...

. He had already donated his collection of law texts to the Law School at the University of Adelaide in 1924. Symon also wrote and published a number of books, including ''Shakespeare at Home'', published in 1905, and ''Shakespeare the Englishman'', published in 1929. Some of Symon's lectures on Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

were published in pamphlet form.

References

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Symon, Josiah 1846 births 1934 deaths People educated at Stirling High School Free Trade Party members of the Parliament of Australia Australian King's Counsel Australian Knights Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Attorneys-General of Australia Attorneys-General of South Australia Members of the Australian Senate Members of the Australian Senate for South Australia Independent members of the Parliament of Australia Scottish emigrants to colonial Australia People from Wick, Caithness 20th-century Australian politicians